Loss is a constant of living. As long as you live, as long as you continue to make connections and entrust others with your feelings, you will always be saying goodbye, always be letting go. And this can be a crushing reality – people can spend their whole lives seeking connections long past rekindling, and the grieving process is different for all of us. This letting go is perhaps not the cheeriest subject for a cartoon, but it is a powerful and deeply human one, and the ways we overcome the continuous goodbye of living can be inspiring in their own right. As is so with Gunbuster.

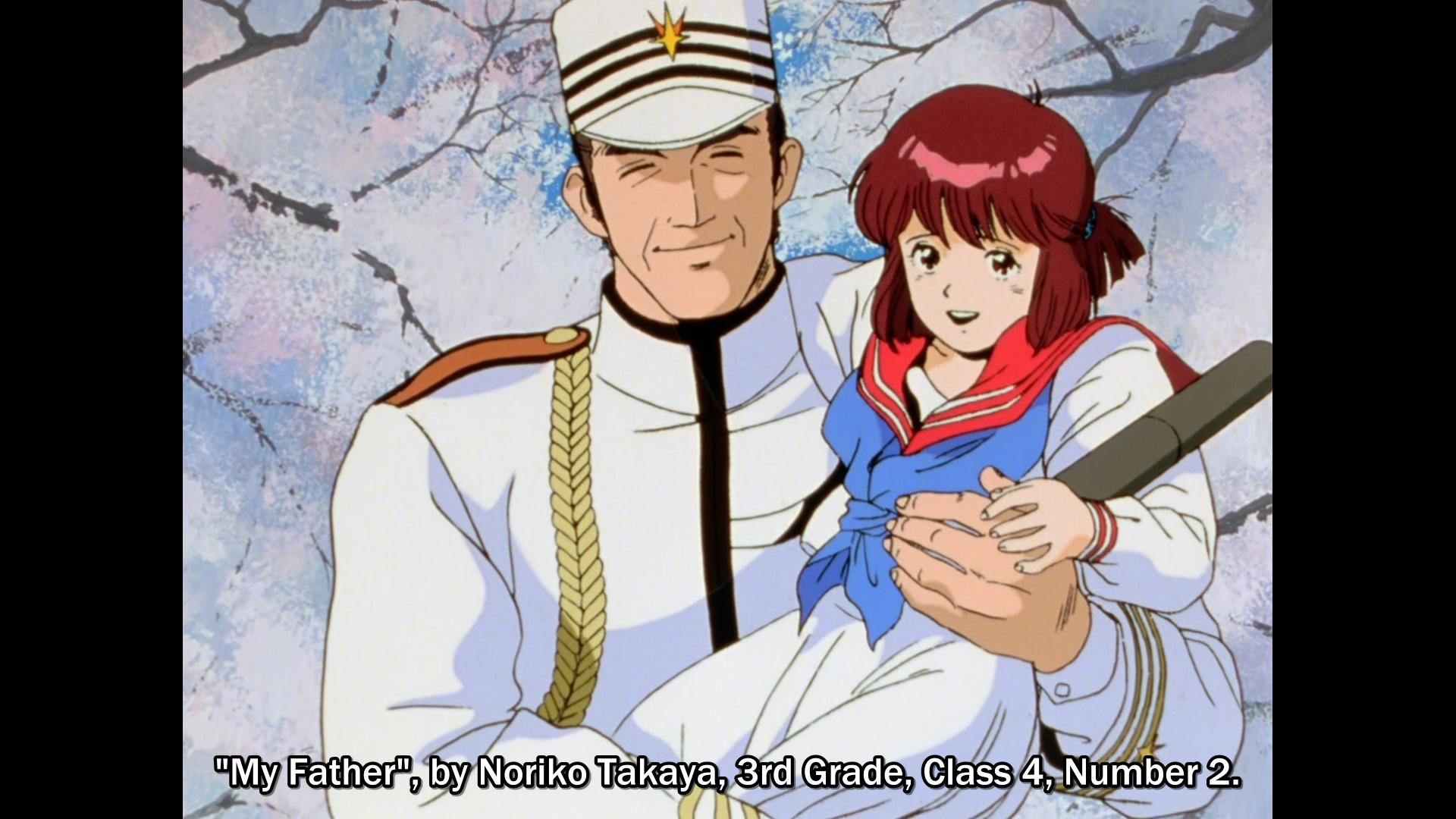

Gunbuster, the directorial debut of Hideaki Anno (who’d of course go on to make all sorts of other optimistic statements about human connection), begins with loss, and loss permeates it. The first image of the show is an old photograph, a captured memory of the father whose death shadows over all the events to follow. The protagonist Noriko Takaya cherishes these memories, and the course of the narrative has her tracing her father’s footsteps out into space.

Gunbuster makes use of space travel in likely the most poignant and graceful way I’ve ever seen. The process of time dilation – how traveling in space at tremendous speeds essentially slows down your personal time relative to the world you’ve left behind – offers an incredible opportunity to explore the disconnect between the lasting closeness of our emotional bonds and the finality of goodbye. Noriko learns of her father’s death years before entering space, but the strange eccentricities of space-travel make her physical closeness to that event mirror its emotional omnipresence. When Noriko is assigned to investigate a high-speed object entering the solar system, she’s shocked to realize it’s her father’s damaged vessel – its own clock putting it only two days past the battle she learned of years before. Filled with hope, Noriko disregards her mission objectives and scours the ship, only to find the vessel empty and bridge destroyed. Though our memories offer an eternal closeness, in practice this feeling is a mirage – you cannot truly turn back the clock, cannot convert those feelings into anything tangible. Ultimately, Noriko’s disregarding of orders has even further consequences – because she lost herself in seeking a bond past recovery, twelve seconds of personal reflection end up stealing six months with her trainees back home. Through time dilation, Gunbuster reflects the cruel nature of grief, and how even those long gone can feel just barely out of reach.

Sometimes loss comes suddenly in Gunbuster – a friend is there beside you one moment, then simply gone, with no warning or goodbye at all. Sometimes you simply drift apart from others naturally, and sometimes circumstances demand this drift. One articulation of this comes through Noriko’s best friend, Takami – throughout the narrative, Noriko finds herself first saying goodbye to Takami as peers, then meeting her again as a new mother, then receiving a message from the daughter of her friend, now her own age. But the type of loss most central to Gunbuster’s message is the loss we accept willingly, the sacrifices we purposefully undergo for each other. As the central character, Noriko is one of the most prominent examples of this – in order to preserve others, she sacrifices virtually all connections she has, condemning herself to the loneliness of unaging space travel. On the personal level, we will always be drifting apart. And so it is not on the personal level that Gunbuster finds hope.

Gunbuster finds purpose in loss through the fundamental, biologically compassionate nature of our species. It is always for the old to sacrifice so the young may live on. Noriko’s father is the first to express this, saving the younger Coach and accepting his death willingly. The show is sometimes extremely cynical about this instinct – early on, the officers describe their opponents as galactic antibodies, cleansing the virus that is the human race. Later, one character questions whether it is even right for them to fight fate, to struggle against something that seems more natural than them – and the only response offered is “the next generation can question. We must survive.” But whether framed in the personal or the universal, there is warmth in this sacrifice – we may lose our individual connections, but we are united by our human drive and spirit. Whether it be through Noriko’s friend begging her to at least save her daughter, or through Noriko hurling herself through time so no-one else would be forced to do the same, that our urge to sacrifice for the young is biological does not make it less “human” – in fact, the show seems defiantly unspiritual, and takes pride in our nature as biological beings, as the human animal. We may lose individual connections, but as a species we are still a single thread.

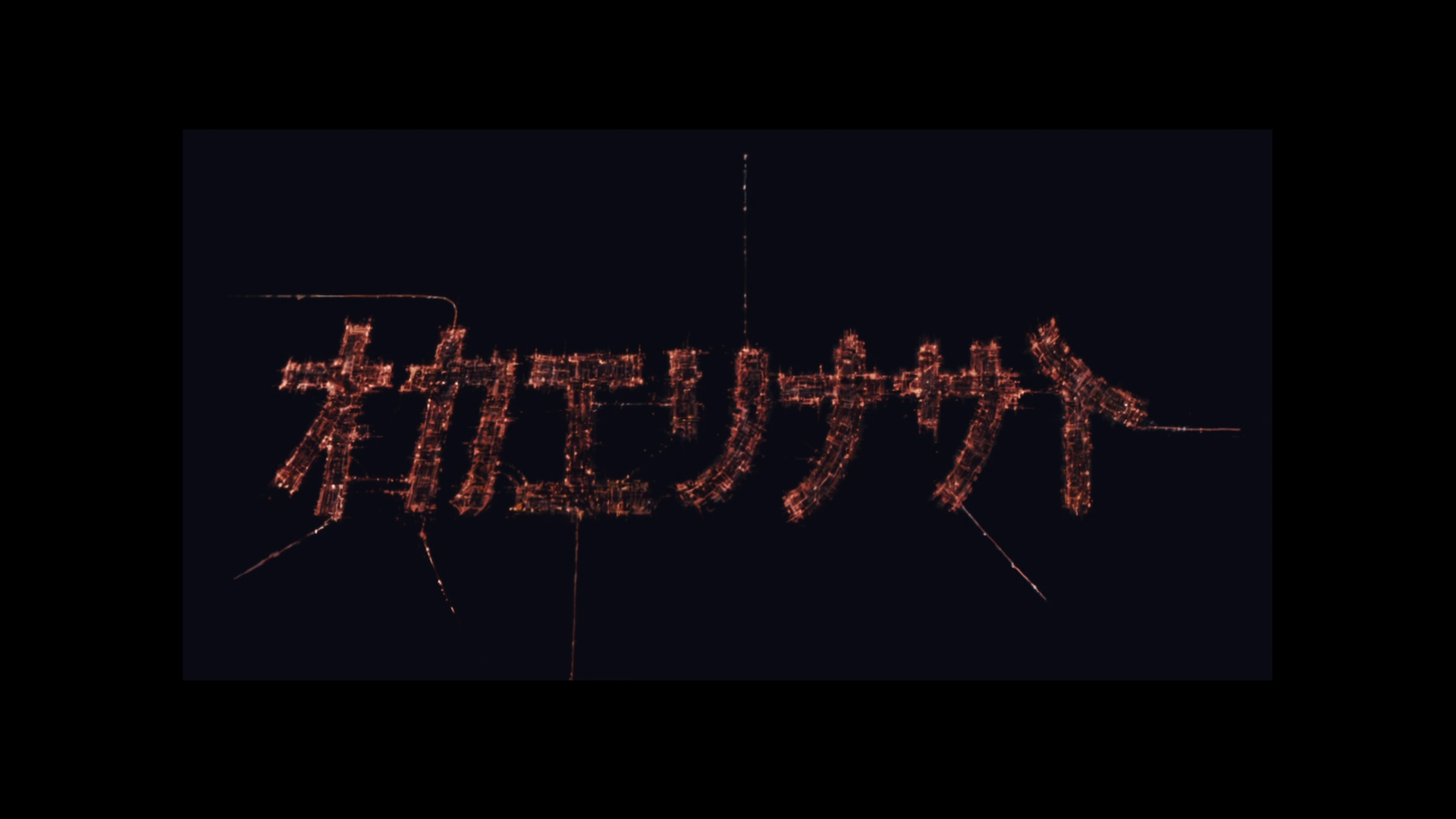

Gunbuster does not have an overwhelmingly positive conclusion. That would be a lie, frankly – it would do a disservice to its own thoughtful acceptance of loss as a constant. Humanity triumphs, but humanity triumphs in the way humanity always has – by trading the old so the new may live. But the last shot is nothing if not optimistic – after abandoning themselves to the forced loneliness of time dilation, our heroes drift back to earth long after everyone they knew had passed, uncertain if there even is a human race anymore. Then, one by one, the lights of earth blink into view, a simulated night sky welcoming them home. Loss is eternal, but as the show says, ‘as long as you keep living, there will always be a tomorrow.’

Great post. And as long as I live, I will NEVER forget that ending. I think it’s one of anime’s greatest moments.

The phrase “you will see the tears of time” I remember well from and will always be well associated with Zeta Gundam in my mind. But I think that phrase actually fits this show best of all.

Yeah, that ending is powerful stuff. It’s remarkable what this show manages in only six episodes.

Gunbuster has the greatest ending of any anime. The only ending comparable is that of Diebuster which was a much weaker series, but its ending does the Top wo Nerae franchise justice.

I’ll be watching that soon! I decided to split up the two of them with Utena, for some reason.

It’s understandable given the emotional and thematic focus of the show, but it’s amusing that if someone only read this essay they would have no idea this is a giant robot show :P.

“PS: Also there are giant robots”

Pingback: Let’s Die Together: Diebuster and Oblivion | Wrong Every Time

Pingback: Top 30 Anime of All Time | Wrong Every Time

Pingback: Top 30 Anime Series of All Time | Wrong Every Time

https://animekritik.wordpress.com/2011/11/22/imperialism-translation-gunbuster-introduction/