I’m finding it difficult to come up with a proper introduction for this piece. But that’s not my fault, I’m pretty sure – really it’s Utena’s fault. Because Utena isn’t just one show – it’s closer to half a dozen all at once, though they’re really all sides of the same show, and though its disjointed pieces seem to spire out in all manner of directions, they end up saying many of the same things. And I’m sure none of this is helping to describe the show, either.

Let’s start over.

Revolutionary Girl Utena is a good show. One of the best, in fact – I’ve heard it described as the shoujo Evangelion, which is a kind of awkward title, but I can get where that’s coming from. In the most reductive view possible, it does indeed do something similar to Evangelion – cataloging truths of adolescence and identity (as well as gender and perception, its own added priorities) in terms of revolution and apocalypse. But framing it as a simple metaphor denies one of the central truths it’s presenting, and why its choice of vehicle is more than just a grand stage for some grounded revelations.

Although it certainly is a grand stage. Revolutionary Girl Utena is nothing if not theatrical.

Let’s start there – with how the tricks of theater and stagecraft define Utena’s goals, Utena’s world, and the lives of those trapped within that egg’s shell.

A Night at the Theater

Revolutionary Girl Utena tells the story of Utena Tenjou, a girl who dresses like a boy and wants to grow up to be a prince. Throughout the course of the story, Utena must do battle with the Duelists in order to claim the Rose Bride, who it is said may just be the key to becoming a prince and capturing something truly eternal.

We’ll get to her. For now, the important part of that description is “tells a story.”

Revolutionary Girl Utena is never content to just be a story – it is continuously aware (and even enjoys making the viewer aware) that it is telling one, framing potential, uncertain truths as a narrative to be relayed to an audience. It does this in a thousand ways, with perhaps the most overt being its playful, consciously overbearing use of motif. The image of the rose is everywhere in Revolutionary Girl Utena – from the roses tended by Anthy, the Rose Bride (a title that gains significance as her own relevance increases), to the rose sigils that mark each Duelist’s ring (another significant detail that points to the true nature of the Duelists), to, most overtly, the ornate rose frame that continuously pops up to frame the action on screen.

Generally, the goal of shot framing is to remove distance, to invest the viewer in drama as if they were there – here, the use of these framing rose sigils actually draws attention to the staged, inauthentic nature of television drama. This is intentional – Utena is always striving to have a conversation with the viewer, and conversations require specific vocabulary. In the case of Utena, this vocabulary includes a litany of visual motifs (the rose, the bird in flight, the bug under glass, the car, going up/going down) that are given direct, overt significance so the show may later call upon them at will. It’s a brilliant example of the power of visual storytelling – because the show works so hard to define its own visual vocabulary (the white rose signifying the prince, the bug under glass signifying both memory and the desire for something eternal memory links to), it can eventually alter a scene’s significance purely through the inclusion of specific weighted visual cues. By forgoing the expectation of “transparency” and overtly acknowledging the creator’s hand in shot framing, the show is able to charge its own storytelling tools with an implicit significance normal symbolism could not achieve. And this acknowledgment of the staged nature of drama through drawing attention to the tools of stagecraft isn’t just an interesting trick of storytelling – it reflects directly on the show’s central themes.

All the World’s a Stage

As I said, in Utena, everything is a performance. This is again made quite literal at times – the show’s most reliable side characters are the “shadow girls,” a group of girls who we only see the reflections of (normally – the show loves to play with its own rules), who each episode act out a simplified, dramatized, and possibly fabricated version of that episode’s theme or narrative. This by itself is a pretty brilliant device – not only does it draw attention to the fact that drama implies spectators, it also acts as a first reinterpretation of the events of the show, and in Utena, perception is key. It even calls to mind ideas as distant and relevant as Plato’s oft-referenced cave, where prisoners trapped in a cave watch shadows dance on the wall and take them for the sum of reality. That’s a pretty elegant metaphor for a great deal of Utena, but for now, let’s try to keep this at least a little grounded.

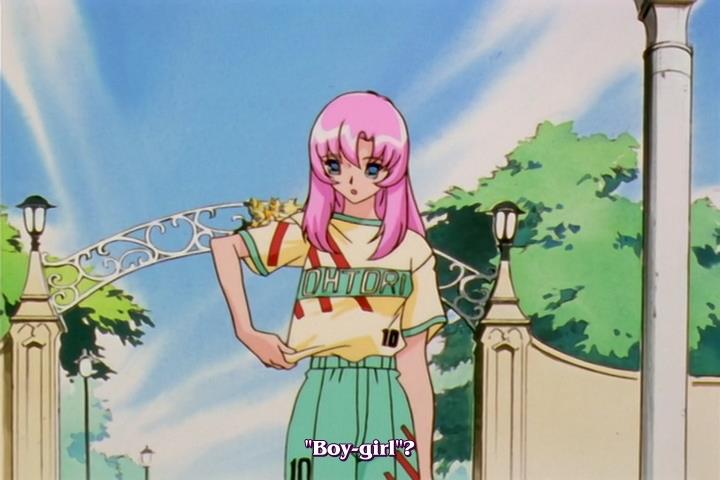

The idea of performance is, like the use of motif, not just limited to cute storytelling games – it informs the entirety of Utena’s world. The “world” of Utena (yes, that word is important – pretty much every word choice is important here) is Ohtori Academy, along with the general realm of adolescence. In this world, you can’t escape performing simply by avoiding the drama club – every person is continuously on display, performing for their classmates, performing their “selves.” The show will never simply introduce a new character – it will cut to them from distant angles, showing the crowds watching and judging, feeding the viewer snippets of their broader reputation. For better or for worse, all the overt happenings of Utena happen under the watchful gaze of the central characters’ endless ranks of peers. And though Utena herself is a Revolutionary Girl, generally unbowed by the whims of the crowds and able to define herself according to a central conviction stronger than the judging feelings of her classmates, others are not so lucky. In Revolutionary Girl Utena, identity can be less a personal truth than a social construction, and no character demonstrates this more than my own favorite character, Nanami Kiryuu.

Conventional Girl Nanami

As a budding socialite and the beloved sister of Student Council President Touga, Nanami ostensibly has it all. Her parties are the fanciest, her fashion the most glamorous, and her obsequious gaggle of yes-girls attend to her every need and opinion. However, even from the start, Nanami is consumed by desire for the one thing she can’t have – her brother’s love and affection. Which isn’t actually as incesty as it sounds – although Nanami frames her feelings as romantic love, in the context of Utena, the love many characters seek really is a pure thing. And not in a storybook romance way, either (though the characters themselves often disagree) – in the way children love each other unconditionally.

However, Touga is not a child, and he doesn’t love like one. He’s a playboy – to him, physical love is largely a game he feels he’s outgrown (in the way only young people can), and initially his only interest lies in the Rose Bride. And in her attempts to win Touga’s affections by dragging Anthy down, Nanami again and again proves the transparency of her image – in spite of her poise and popularity, she’s a petty, vindictive, selfish, insecure, childish little girl. Though she starts off in the role of an antagonist, the show never really treats her as a threat – her schemes are all easily foiled, her desires are disregarded and mocked by the narrative, her whole existence is turned into comic relief. And through the course of her own dedicated episodes, we see that she, more than any other character, demonstrates the degree to which identity can be not just a cloak we wear, but a cloak not even sewn by our hands – one constructed by the perceptions of society itself.

The episode that makes this most explicit is, ironically (and somewhat unsurprisingly, given Utena’s sense of humor), perhaps the most ridiculous episode in the series – the cowbell episode. When Nanami accidentally receives a cowbell as a gift, she takes it to be a fancy necklace, and wears it with pride. However, through the course of the episode, Nanami’s insistence on the beauty of her cowbell ends up actually turning her into a cow. The message here is clear – the appearance she displays ends up dictating her actual nature. Utena is not content to illustrate a simple-minded “don’t let others or your appearance define you” message – it knows the effect of the outside gaze is powerful, and it knows our context and social appearance can end up dictating our own fundamental nature. Because Nanami’s identity is so completely contingent on the opinions of others, she actually becomes whatever others’ perception of her dictates she must be – given the garb of a cow, her own self-confidence is not strong enough to convince her she’s really a human at all.

Later Nanami episodes further drive home the weakness of her own self-generated identity, a weakness that ends up aligning her with the “normal” people she projects such disdain for. In one episode, she wakes up one morning to discover she’s apparently laid an egg, and spends the rest of the episode panicking over whether this is the “normal” thing to do. And in one of her last appearances, she discovers that she’s apparently not Touga’s sister by blood, a revelation that threatens her entire sense of self. When she falls into despair, Utena attempts to comfort her by declaring her feelings equally valid now as they were before – but to Nanami, her feelings are only valid so long as they’re supported by the outside structures through which she confirms her identity. “My brother was part of who I was,” she says – devastated that fortune has stolen one of the only truths she thought the court of public opinion could never take away from her. And the final blow comes when her brother calls her “ordinary” – judged and found mundane by the one person whose opinion she admitted to valuing, she desperately asks Utena, “What’s left for me? Am I just one more fly in the swarm? Anything but that…”

While Utena assumes everyone in her world is an active agent, Nanami does not have the luxury of such ideals – she is a product of the communally-created identities that define the show’s oft-seen, rarely respected underclass. Unlike what Utena aspires to be, she is unabashedly a young human girl, and her greatest fear is to be lost in the glow of the stars that surround her. Fittingly, at the very end, she is the first to surrender the crest that marks one as a Duelist – as a seeker of miracles, as a believer in something eternal. And it is that quest for something eternal that brings us at long last to the show’s central character, Utena Tenjou.

The Girl Who Would Be Prince

Utena’s an interesting character for a variety of reasons, but it all starts with the basics. When she was a little girl, she lost faith in the world. However, a prince came along and gave her conviction, leaving her with a special ring and promising they’d meet again, just so long as she never lost her strength and nobility. So impressed was she with this prince that she decided to become a prince herself. But was that really such a good idea?

So goes the fairy tale the show comes back to time and again. Though the words remain the same, the message never does – in a show obsessed with performance and perception, the meaning of words can shift even as their base nature remains consistent. Words like “prince,” the traditional storybook male savior, a word that ultimately comes to signify both less and more than its stated definition. From the beginning, Utena’s desire to be a “prince” points to the serious bone this show has to pick with traditional gender roles. Even the show’s ornate style contributes to this effect – the flowery framing that’s typically a hallmark of “female-oriented” manga and anime is here used to convey traditionally “masculine” power, such as the seductive power of a potential male prince, or Utena herself as she trounces male classmates on the basketball court.

Utena is consistently cast in “masculine” terms, from her chosen form of dress, to her adoring female fans, to her athletic prowess and skill as a swordsman. However, to Utena, all these choices are a perfectly legitimate expression of self. In fact, whenever anyone expresses surprise about Utena acting like a “traditional” girl and “performing” girl, Utena responds with a defiant “but I am a girl” – to her, her standard behavior and representation is a completely valid expression of “girl.” Which all points back to the show’s obsession with spectators and performance – in the context of a show that emphasizes how much we all “perform” our personalities, the arbitrary, “performed” nature of gender roles is that much more apparent.

But of course “prince” is not a word only relevant to Utena’s thoughts on gender – a “prince” is something more than that, something every person seeks. Utena’s “strength and nobility,” her black and white moral certitude that often comes across as stubborn naivety, is a reflection of her once meeting a prince – of her being shown “something eternal.” While each of the characters in Utena are in turn characterized by their own colored rose, the prince is represented by the white rose – an absence of color, an expression of absolute purity. This purity cannot exist in the real world, but it can be believed in – which ties into Utena’s other central metaphor, the quest for something eternal and the edge of adolescence.

An Eternity of Youth

“If it cannot break its egg’s shell, a chick will die without being born. We are the chick. The world is our egg. If we don’t crack the world’s shell, we will die without being born. Smash the world’s shell! For the revolution of the world!” So say the Student Council each time they ascend to their meetings, and so do they really mean. The characters of Revolutionary Girl Utena all exist within a strict, limited world – the world of adolescence, where their own sexuality is a strange new weapon and the youthful dreams of their childhood struggle with the messy realities of relationships and perspective. Each of the council members seeks their own “something eternal” – something pure, something that can survive the ravages of growth and experience.

But as with Nanami’s “pure love” of her brother, the characters do not initially recognize the nature of their own desires. Jury, the fencing captain, ostensibly seeks to kindle a relationship with an old crush, and cherishes the locket that holds her friend’s picture – but through the course of her trials, we see that what she really values is the locket itself, the token of a memory that cannot be tarnished. Each of the council members seeks such an eternal, ungraspable prize – each has their own cherished token of the pure relationships and ideals that defined their childhoods. And as their attempts to preserve these tokens under glass are thwarted by their continuously muddled relationships and the true, imperfect natures of the people they wish to idolize, Utena’s own conviction and adherence to the nobility of pure princehood inspires respect, envy, and even love. And as each of them grow to accept the imperfect nature of the world around them, they entrust their hope for something eternal in Utena herself.

Nobility and Strength

Not that Utena is actually some austere, emotionless idol. Far from it – she’s blunt, headstrong, naive, and often lacks the emotional insight to offer meaningful advice to her friends. For a great deal of the show, her desire to protect Anthy is in many ways no different from the selfishness of the other Duelists. Though she chastises them for seeking the power of eternity while not seeing Anthy as a person with her own desires, she does exactly the same – she always does “what’s best for Anthy” according to what she thinks is best. Which Anthy is certainly okay with – as the vilified Rose Bride, she is essentially forced to represent femininity as an ultimate passive force – something to be drawn upon and used, the one who suffers for the sake of the masculine Prince. It takes Utena a long, long time to come to two realizations – first, that her protection of Anthy is more a reflection of her wanting to put on the successful image of “what a prince would do” than an actual expression of her understanding of and concern for Anthy, and second, that playing by the rules of “what a prince would do” is a sucker’s game from the start. Only by acknowledging the power and necessity of Anthy as an equal partner, not a prince’s tool, can revolution be gained.

In the end, Utena meets her fabled prince, or at least the man who once appeared as one. He takes the form of Akio, the original Prince to Anthy’s Rose Bride, the one who is meant to bring the world revolution. He condescendingly congratulates Utena for making it as far as she did, and gamely offers to let her be his princess – but Utena refuses. And Anthy, still caught in the system that rewards princes for their alleged necessity, betrays Utena, granting Akio the sword of the prince. “You could never be my prince, because you are a girl,” Anthy whispers – and maybe this is true. But what is certainly true is that Akio fails to bring the world revolution – as Anthy bears the burden of the world’s scorn, his prince’s sword shatters on the gate that leads to eternity.

The Power to Bring the World Revolution

And Utena stands. Unsteady, without the weapon of the prince, she shoves Akio aside, approaching the gate. “Without power, you are destined to be ruled by others,” cautions Akio – clearly he is not a man who believes in something eternal. But Utena, though she has loved and lost and grown and is clearly far too human to represent any idealized “pure prince,” does have faith – at least in some things. With her head against the door, she admits that her moments spent with Anthy were the happiest of her life – and the gate opens, and Anthy is set free. Not by a prince’s hands – a prince’s hands are ephemeral things, and give you no power of your own. Utena’s declaration does not drag Anthy to freedom – it simply wakes her up, and lets her know she has the right to seize her own freedom. Utena offers a hand, and Anthy takes it. And though Utena disappears in the destruction of the fabled castle in the sky, the world will never be the same.

Revolutionary Girl Utena has a somewhat ambiguous ending. In the halls of Ohtori Academy, Utena is talked of in vague whispers – her exploits are remembered, but they are recalled as others saw them, transformed and interpreted through the many lenses of the crowds. Akio believes nothing has changed at all – as he sorts papers and plays the role of Academy Chairman, he confidently tells Anthy to prepare for the next wave of soon-to-be-disillusioned Duelists. But Anthy smartly corrects him – “she’s not gone. She’s merely vanished from your world.” And Anthy packs her bags, and Anthy walks away, discarding her Rose Bride red and wearing a bold pink dress, firmly declaring herself to be Utena’s equal. We don’t see Utena again – Anthy declares she’s going off to find her, but it’s left ambiguous whether she’s truly gone.

Fortunately, in the context of Utena, that’s really not much of a handicap. Because as every other piece of the show continuously implies, belief dictates reality. Just as the characters literally become what others expect of them, just as the show’s visual language continuously flips between character’s mundane selves and imagined ones, in Utena, reality is as much our collective belief as it is our objective geography. Utena may not have destroyed the mundane reality, but through her actions she inspired faith in a better one, one not chained to the false idols of princes or defined by the capricious whims of the crowd. In a story obsessed with smoke and mirrors, trapped in the mire of youthful expectations, and burdened by a cynical understanding of how difficult it is to control your own identity, ultimately revolution is achieved through the simplest of actions. Utena admitted an honest love, and that sincerity changed the world.

Utena in Review

But hey, that’s just my view of the ending. Utena is a rich and ambiguous show, and it rewards viewers for bringing their own priorities – regardless of how much you invest in it, questions will always remain. What’s up with the stopwatch? Was Anthy redeemed, and did she need to be? Are the stars we see around us merely a trick of perspective, like the eternal goals we create for ourselves? The show is vague, and all I can offer is my experience of it – but that experience was a great one, and I hope you’ve found something new in my telling of it. Like Utena demonstrates, our experience of stories is an eternal interpretation, and our personal realities are the richer for it. We can’t dictate the stories we leave behind, but we can at least give people something to talk about.

Good essay. As for the stopwatch, I noticed that he (the blue-haired buy) typically seems to be measuring how long people were speaking for (at least that’s what he’s doing in the student councile meetings). I guess this symbolizes his fastidiousness and need for a sense of control.

That makes sense – it definitely fits with his “neat and proper gentleman” affectation. And also how his appearance of control is largely just an appearance, too.

I thought that it was very explicitly “overtly acknowledging” the hand of the creator. As in the way the lengths of different cuts are constructed from lines of script, by roughly timing how long it takes to say the line with a stopwatch. Maybe it’s just that I recently watched shirobako…

I think its a way to demonstrate how time doesn’t exist in Ohtori and how the only way he has to approach this obvious yet ignored reality is through evidence.

I wish I actually liked Utena. Don’t get my wrong, I think it’s a great series – incredibly rich, highly interpretive, and clearly very lovingly made. I had fun with many of the characters, liked the soundtrack, and in general thought that the storytelling was very fine work. But in terms of purely personal enjoyment… not so much. I expect Utena fans will be stoning me for this, but I just didn’t care all that much for the series on a subjective level.

I definitely understand that feeling – in spite of all my praise, it did take me three months to get through, after all. I felt the same way with Shinsekai Yori – “this is really good stuff, and we rarely get shows like this. Why aren’t I enjoying it more?” Our relationships with shows are weird.

I’m still not sure how I feels towards this show. I must rewatch it again, sometimes.

But I don’t think its goal is to be “enjoyable”. Or if it is, it’s more on an intellectual level. The enjoyment doesn’t comes from Utena itself, but from the way we interpret it.

I always had the impresssion than the author had more fun with it than us.

In a way, all the interpretations about of this show are part of the show. Watching evryone trying to search a hidden meaning, trying to solves a puzzle that may not even exist, or more likely have a near infinity of solutions must be enjoyable to see, I guess. And even if there is no clar answer, it’s also enjoyable to try to find it.

I finished Utena in 3 days. Finished it yesterday, actually. And don’t get me wrong, I am NOT a fast anime watcher. I’ve been watching Galactic Heroes for well over 5 months now (Adore that show, 10/10 and all that, It’s just a lot to handle) but Utena was something else. I’ve been nonstop watching amazing shows for the past few months now (my top 50 is a totally different thing now, so much so that the one on my site is viciously outdated) yet none of them were as good as Utena. To me, it’s not a show that you respect but don’t like; it’s a show that I respect and love. I’m also just wondering what you mean by personal enjoyment? Like, what are some anime you really enjoyed? To me, respecting and finding heart in a work creates enjoyment.

Great essay. Pretty much covered all the important themes in an interesting light. Plus the homage to best girl Nanami.

For my ideas on your last questions:

For the stop watch my idea of it is that it denote an obsession with the present. His need to be effective and to not waste his time of youth maybe? Ironically losing time trying to gain more.

Was Anthy redeemed? uh sure. It was pretty clear that Utena aspired her to become more then the reflection of what people wants. She needed to be given the opportunity to change. The rest of the student council playing badminton in the end will probably follow her some time after, has they also were inspired.

I sure has hell hope the stars were meant to be a trick of perspective that only seem unreachable for most. Otherwise it would be a pretty grim message. That there is really a natural select elite.

Just bouncing off your “obsession with the present”, that goes along with the stunted adolescence of the students at Ohtori Academy and I think there’s even a line about how they have no future there.

A couple other commenters have noted that he apparently times various elements of the conversations he’s taking part in, which seems to make a lot of sense given his “prim and proper” personality.

On the stopwatch, I’ve seen interpretations that point out the similarities between Miki and Quentin Compson from (The Sound and the Fury)… The time obsession and the pre-occupation with his sister’s innocence would be great tip-offs.

You should stop doing those one episode write ups, because this stuff here is so much more better.

I’m kind of moving in that direction, though these are a lot more work, and obviously require shows that are worth the effort.

Yeah, thinking the same.

Am thinking the same and doing the same. But it’s german tho’ (DU-dun!), and it is in a forum where wwe are like 10 persons and everony gives like a little snooze on what they are looking in the season, funnily we got nearly everything covered. So it’s like a week in review stuff + when someone finishes something with a general blabla upon it.

I like Utena. I respect Utena. But I just can’t love Utena. The show was fantastic from an academic standpoint, and it makes for great material for essays like this. It has amazing symbolism, great comedy, interesting characters, tons of motifs and visual clues, and a myriad of themes and lessons, as you so skillfully pointed out. But to me it lacks balance. It’s not a problem of being overly ambitious, or overly overt with their messages. I applaud both of those things. However it seemed to let it’s entertainment value as a story take the back seat to it’s messages and symbolism. This is something I frequently have a problem with when viewing shows that are highly regarded like this. Utena has much better balance than say Paranoia Agent (which completely forsook it’s story for it’s message), but it still fails to firmly strike a chord with me. I enjoyed it, it was fun, it was interesting, but I was not engrossed. In that way it was the opposite of it’s successor Mawaru Penguindrum which I felt had the story overshadow the symbolism and message making it less coherent. It’s still a great work and I hope we can continue to get more anime that strive to have this level of ambition (You mentioned Shinsekai Yori somewhere else in the comments, and for me that is an anime that struck a proper balance and pulled me in). Everyone has their own personal tastes so perhaps some might have found the story to be engrossing, but the more anime like this that are made, the higher the chances that someone can find one that fits for them.

I don’t think it’s really a balancing act where more focus on one works at the expense of the other – I think Utena’s just an inaccessible show. It has a very specific sense of humor, it has a repetitive narrative structure, and both its shoestring budget and debts to genre formula are clear in the repeated sequences throughout. I don’t think any of these choices are message-critical, just like I don’t think Shinsekai Yori’s pacing and character problems were a necessary choice – I think they’re all just “flaws” that will justifiably alienate certain audiences.

Not that I’d condemn either of these shows for their choices. I agree with you, we need more weird, auteur stuff – it won’t speak to everyone, but it will mean everything to someone.

Interesting. I was completely engrossed by Utena. But it does appeal to a very specific sort of taste.

The “light entertainment” value for me was largely in the absurdist and surrealist sense of humor; you can watch it just on that level. There’s actually an element of camp in the use of genre formula and repetition for the purposes of subversion (such as the fact that all three clip shows actually contain totally critical plot points).

If you don’t appreciate those types of humor, Utena could be quite merciless emotionally (if you are catching the subtext, which is ruthless), or even boring (if you aren’t). But for those of us who love those sorts of humor, it’s perfect.

I can’t get into Evangelion for a similar reason; I respect it and like it but something about the storytelling choices just doesn’t hold my attention. It’s not funny (to me, anyway). Utena is funny, even in the most emotionally gut-wrenching moments (of which there are many).

By the way, thanks for this essay; it’s really good. Better than stuff which gets published in academic journals and magazines good.

Pingback: Top 30 Anime of All Time | Wrong Every Time

Pingback: Top 30 Anime Series of All Time | Wrong Every Time

Fantastic essay. I love your insights. This really is an amazing show, and I will probably be watching it again soon with your analysis in mind. I’m surprised to read the comments of those who didn’t really get into the show; I enjoyed “Utena” immensely and thought its charm, subtlety, and complexity were all thrilling. The emotional weight of the ending was incredible.

Thank you! And yeah, Utena only gets more powerful for me in retrospect. I get all misty whenever I think of that moment with Utena lifting herself back up.

does anyone have any idea what the significance of Mikage rejecting Tatsuya in episode 19 was?

That Tatsuya’s desires didn’t bring him to the point of insulting Wakaba directly. The feelings he had for her were too shallow, and while they were problematic, they weren’t the type of toxicity that the student council members had with everyone else.

Wow, your appreciation of the ideas in the show and how it expresses power relationships between masculinity and femininity is terrific. Your ideas about Utena wanting to be a Prince and ultimately what that meant for the relationship between Utena and Anthy were things I hadn’t considered and really make good sense. Awesome essay.

I may be a year behind in reading in commenting on this post, but yes! I love it! These are exactly the kind of points that float through my head on watching, but my grasp on them is always too tenuous because I am engrossed in so many other aspects of what’s going on in the show. I am both an Utena-lover and an Evangelion-lover – shows with the crazy, meaty metaphors, agendas, philosophical points, etc. Thanks for this post!

One thought – in regards to Anthy and redemption – I would think that the idea of redemption and/or the need for it and its occurrence might be a viewer construct. If we think of Utena as a show about adolescence and identity, as the beginning of the post states, then when reduced to that context, I would find redemption irrelevant, unless you are feeling guilty about something you did in high school 😉

Everything during that period, in real life, takes on a sheen of high drama, and so betraying your friends, letting your behavior be controlled by others, and all the other kinds of things that people do in high school may feel dramatic and consuming and earth-shattering, but as we enter into adulthood, I think hardly anybody feels the need to make up for being a less-than-stellar person during that time. We are all figuring it out and some people do a better job of holding on to their core values than others (Utena vs. Nanami?) So, if Anthy’s actions and behaviors are just interpreted in the context of our world and not so literally, as in the world of Utena, then I don’t see any need for the question of redemption.

I’ve thought it was intriguing that Nanami quite easily escapes the school, when she goes hunting for spices in India during the curry episode. Like the rules didn’t apply to her.

Who says that India isn’t a part of the school?

、貢献のためよろしく。ポスト | すべてのすべてのために、この中に入れて感謝の意をあなたが持っているあなたが持っている

Thank you for this great essay. Would you consider writing one specifically about the Black Rose Arc? It is by far, in my opinion, the most interesting arc in the series. It’s an arc I keep going back to and keep rewatching, and each time feels like a new experience. I would love to read your interpretation of it.

there should be a genre for symbolic anime

Also Akio’s car seems to be able to go the speed of light: and what could be a better metaphor for “the end of the world” or /”things as they really are” as Saionji puts it.

Also the shadow girls represent the Socratic cave notion that the sun (the shining thing/ etc.) is the unattainable singular truth, while shadows are the many versions of untruth and rumors.

Wow, upon reading this, I came to sort of understand what Utena is portraying. I only watched the anime but still I get the feeling that you need to watch it if you are mentally prepared and have a certain level of maturity. Just like watching Ghost in the Shell.

The anime was in deed filled with so many vague messages. Side conflicts and comedic reliefs. Still through the course of thr series I always almost every episode think why am I still watching the show because every next episode so many additional questions come to mind. The duels and duelist. Anthy? Who she is and where she came from. Why does she have powers? For what do they desire the eternal prize that will be rewarded? Where is the yuri part of the show? Because not until when Anthy said to Utena she wants to have friends they became connected to a higher level. Still then, Utena seems to still be swayed by the boys. Maybe she justs a bisexual.

Going back, the yuri tag is not the main highlight but the message it portrays. I mean some/most of us undergo being an adolescent in her/her highschool/college years.

The intro where it talks about a chick breaking its egg is something like graduating or becoming an adult. Where you must break the things you were used to do when you are still younger and be ready to take future responsibilities. I mean I think that must be it right? Cause if its about learning how to cook I dont know anymore.

Also the series tackles on many problems teens go through during those times. Some characters became tainted and lost before going/breaking from their school. The prince in the story tells a young girl to preserve herself. The message is pretty simple. Study well and respect everyone and your body. Lol.

Also it highlights the insecurity of a girl. Who reflects hersekf as what other would want her to be. Throughout the long course of the series. Anthy only does what her owners wants/thinks. But at least in the end Utena was able to identify her mistake. And Anthy finally was able to recognize her self worth although nit so much because she still stabbed Utena with the sword.

So to make the story a little less complicated. I think the series of duels were the test/exams that we need to pass during the school years. So in the animr Utena is the first one ti graduate while followed by Anthy. The other guys justs fail and retake the semester.

On Anthy finding Utena. Anthy decides that she will no longer take part of Akio’s bad influences and practically wants to break free from the school. (I thought of this because Akio was still young when he met Utena. And he was already studying in that school. Which means he didnt graduate at all) Since Utena graduated first and in the anime there were no sign of communication device. She will now look for the girl who changed her views and motivated her to change.

The ending was quite good but still a little lacking – because I lack imagination. I could have just wished that they saw each other again but that would ruin the ambiguity and vagueness the show was embracing.

Overall this is an anime not for everyone but I sure once you watched it you will appreciate its unique beauty. I am literally still wanting more after episodes of the final battle.