Mushishi is a broad and ambiguous collection of vignettes, and it offers few easy answers. In light of this, it seems silly to try and impart any “one truth” of Mushishi’s narrative – everyone will take something different from its stories. In light of that, I hope my audience will forgive me for my own somewhat selfish experience of this series. Mushishi can mean many things to many people, but it means one very important thing to me.

“When it’s all gone, something carries on.

And it’s not morbid at all – just when nature’s had enough of you.

When my blood stops, someone else’s will not.

When my head rolls off, someone else’s will turn.

And while I’m alive, I’ll make tiny changes to the earth.”

–Head Rolls Off, Frightened Rabbit

The Boy Who Conjured Life

The “Hand of God” is what they call it. A strange and perhaps unnatural gift, that grants its bearer the power to conjure life from art. Whatever the bearer draws with his gifted/cursed hand takes form, drifting off the page and adopting a life beyond its creator’s intent. In truth, it’s not anything all that unusual.

All art creates life. As a very young man, I was surprised and elated to discover this – that the things I could create, could conjure from experience and craft and will, would actually take form, adopt a life of their own. I wasn’t a particularly social child – in fact, I’m not a particularly social person. What I see in the world often seems different from what those around me see. Where others see connections, I see the tiny embers of stories, floating wisps that might be the tails and limbs and unruly organs of writing waiting to be. These visions can seem more “real” than any other reality – be it through a pair of eyes that see far into the distance, or a vision that explains the phantom pain which seems so mysterious to others, these perspectives define their bearers’ realities. Mushishi is full of such people, whose strange visions of reality set them apart from even those close to them. Who, like Tanyuu, take of the mundane and human experience of the world and bleed out something new. Who, like the man chasing his father’s rainbow, turn a passion into an obsession, into a life pursuit.

The Stone of Great Misfortune

The Hand of God is perhaps an unhappy gift. Though it allows its owner to bring their personal visions to life, it also creates distance. The boy who bears it is separated from society, left alone in the mountains, and perhaps that is for the best.

The gifts of those touched by Mushi are a strange and ambiguous lot. Just like any act of artistic creation, they can often offer great fortune for others even as they impart a heavy toll on their wielder. Like the woman with the far-seeing eyes, who tells futures she cannot prevent until her prescience overwhelms her ability to live. Or the girl who chooses to live purely as a conduit for this insight, the Ikigami, abandoning the hectic dangers of the human world for one of slow, pure connectedness. Even when the gifts of the Mushi are purely positive, they are always different, and invite suspicion. And far more often than that, they aren’t positive – or at least not purely so.

The most pure expression of this ambiguity might be found in the story of the inkwell-crafter. Though she trains hard to create objects of beauty, ultimately her breakthrough comes when she is briefly touched by a Mushi’s influence – and the stone she crafts is a masterpiece. But though she intended it only to express her own ability, the stone moves beyond her grasp, causing suffering far afield even as she tries to stop it. We cannot control what our artistic creations will mean to others, how they may help or hurt. And the sharpness of this vision, both in how it makes us strange and how it reflects on those around us, can very easily breed distrust. Meaning isolation is often the natural lot of a life dedicated to the arts.

The River of All Life

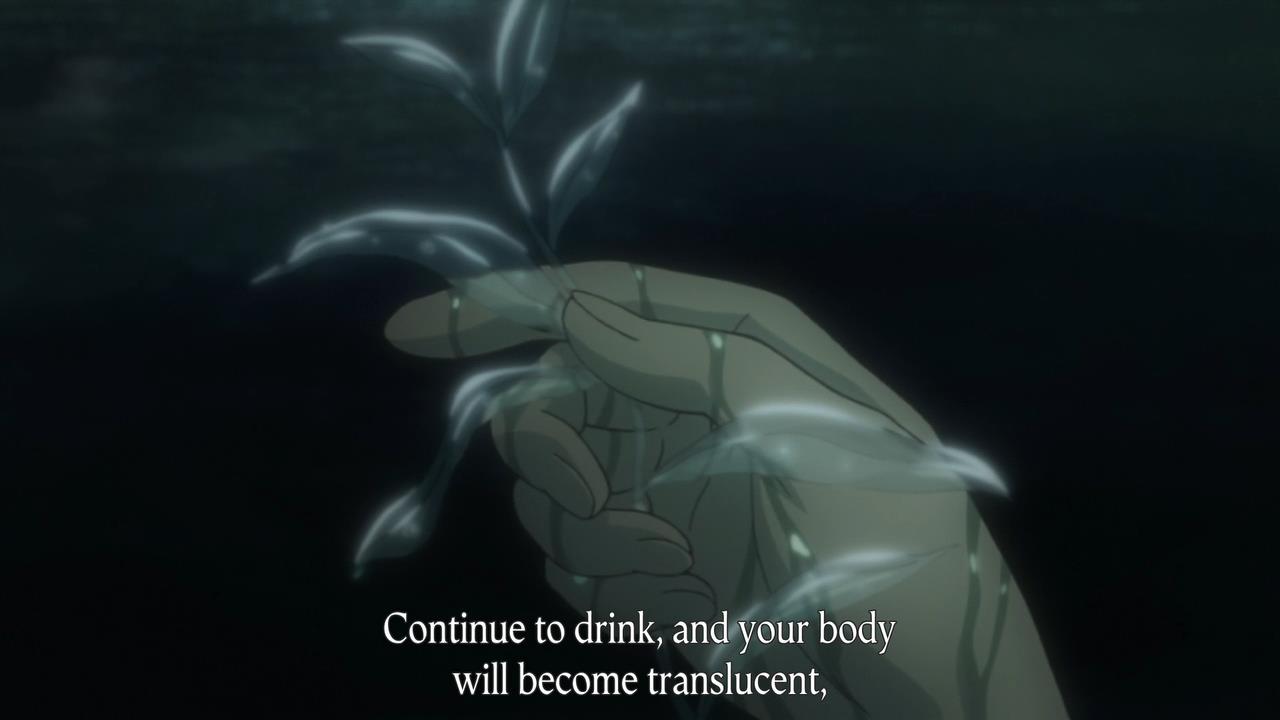

The source of the Hand of God’s power is left vague, but the insight Mushi tap into are strongly represented through the presence of its bearer’s grandmother, Renzu. She once drank from a cup offered by the Mushi themselves, and so drifted apart from mundane humanity. Though this gift offered her both a glimpse of communal wisdom and a kind of immortality, it separated her too far from human nature, and now she can only observe, no longer able to be an active participant in the lives of those she cares for.

The true nature of the Mushi is an open question in this show, opening the door to such self-aggrandizing reads as this very essay. It is described as “a kind of living organism more fundamental than humans” – something closer to a communal nature, to a common insight or consciousness. The events of each story confirm this, and offer their own elaborations and cautions regarding this base nature. The universality of the Mushi is a kind of collective awareness reminiscent of Zen philosophy, where the nature of life around you and the passing of days is all the insight there could be, all that there is. Though this broader perspective (and perhaps even the outsider status it entails) is actually what grants those touched by Mushi their insights on the nature of the world, it also presents a constant danger. Step too far into the Mushi’s world, and you will lose any sense of an individual self. The girl chosen as the Ikigami embodies this, and the girl who almost joins the swamp comes close – having lost or devalued their connections with the human world, they embrace a communal existence that denies their mundane, human nature. Get lost in your own visions, embrace the insights of the Mushi too deeply, and there will be no self left to come back to.

The Island of Rebirth

Fortunately for Renzu, the boy possessing the Hand of God is visited by a Mushishi – a chronicler of Mushi, who catalogs this strange world and deals with those on the borderline between Mushi and humanity. The Mushishi Ginko is able to recognize the humanity in her, and gives her a choice few could offer – a chance to either complete her passage into the egoless immortality of the Mushi, or to return to life as her grandson’s human caretaker.

The question of immortality, and of the purpose of life more generally, is a consistent refrain in Mushishi, and the island of rebirth (where those nearing death can be reborn as children) exemplifies this question. As a girl’s mother is boated away to be reborn, she begs for her daughter’s forgiveness, saying “Forgive me, Mio. I am afraid of vanishing.” Mushi can grant immortality of a kind, but it is a fractured gift, often expressed as the half-life of the girl who falls from the bridge, or the girl who becomes the Ikigami. Mushishi does not seem to cherish such ghosts, which is in keeping with all of its thoughts on artistic creation. We cannot make copies of ourselves to outlast us – we can only live as we are, create what we can, and let those beyond us interpret what we leave behind. Like the master Mushishi, who dies in order to protect his mountain, but has a single disciple to carry on his legacy. Ultimately, it is this form of legacy-interpretation that even the island of rebirth must be content with – though Mio’s mother is “reincarnated” through her granddaughter, that girl is her own person, just as our art has a life of its own. Mio’s worries that she is simply raising a copy of her mother are assuaged by the ways her daughter proves her own influence, itself a far more natural form of immortality. Whether our heirs are as precious as new daughters or treacherous as the cursed inkstone, we cannot fully control the legacy we leave behind.

The Girl Who Fell into the Sky

In the end, Renzu agrees to return to the human world. In fact, it is her grandson’s very gift that draws her back, his power of creation recreating the tool that distanced her in the first place. These two worlds reflect on each other in this way, and each gives substance to the other. Those touched by the Mushi need human contact – both to maintain a tether to this world, and to give their insights meaning and purpose.

This need for human contact is perhaps best represented by the girl who fell into the sky. Accidentally ensnared by a Mushi, and rescued only by the Mushi-awareness of Ginko, when she returns to human society, her existence as a distinct individual is still fraught. Trapped on the border between realities, it is only through the faith of her lover, who believes in her in spite of all evidence to the contrary, that she is able to maintain contact with the mundane world. When she feels she is not valued by her lover, her existence wavers – it is only by continuously reaffirming the value of human contact that she is able to live as an individual.

So it is for all those distanced by their visions – though solitude comes naturally, it is only through human connection that happiness can be found. The story of the man who painted his mountain goes even further than this – though he strays far from his home and connections as his art career unfolds, he is eventually undone when the village that was his home is buried in a landslide. Without that touch of human connection, his art has no spark, no humanity in it. Whatever insight we may draw from the Mushi, it must be tempered by our connection to other human beings, or it has no universality and soul. What purpose does art have if it is a solely private gesture? Though Mushishi’s characters live on the edge of society, it is always the edge, and not wholly removed from it – though the Mushi-sight is an isolating gift, this isolation must be fought for the gift to bear meaningful fruit. Just as it is the act of being observed that turns an aesthetic object into an art experience, so too is it the act of being valued by others that gives us value, vitality, and life.

The Sound That Wasn’t There

The boy with the Hand of God does not begrudge his gift – he is simply unhappy he could not share his sight with his grandmother. Though she loves and protects him, she cannot understand his powers, and thus there is always distance. But this is not painted as a good or a bad thing – it just is.

Often it seems like the characters of Mushishi would be better off without their gifts. They cause pain, they create distance – but as much as the characters rail against them, the show does not condemn Mushi-sight as a true burden. Like the Mushi themselves, the strangeness of these individuals just is – if it were gone, they would not be who they are. Painful or not, these gifts are precious – and the characters of Mushishi occupy the space between because it is so very rewarding to bring from the realm of Mushi to the realm of people. To live with distance is terrible, but to surrender entirely to the Mushi, or to give up their strange realms after once seeing them… such fates are worse still. The woman with the far-seeing eyes comes closest to expressing this, saying “I’m afraid of losing the light, but I’m more afraid of a world that’s entirely white. If you could see everything, and change none of it…” It would likely be easier to surrender to the Mushi entirely, and live as the Ikigami… but the human instinct drags us back. Perhaps their definition comes less from their base nature, and more from this very insistence on their execution – perhaps what makes an artist is not talent, but the inability to live as anything else. These gifts are meant for creating meaning, for sharing beauty with others. Their pain is a part of their responsibility, and only makes the importance of building bridges back to humankind that much greater.

The Man Who Walked Between

After helping to restore the necessary human connection between the boy with the Hand of God and his grandmother, Ginko once again sets off into the wilderness. A natural attractor of Mushi, he cannot stay in any one place himself – instead of living within society, he must travel through it, wandering its edges and connecting with those who lack connection. Though he offers precious human contact, he himself lives like the Mushi – when asked what the purpose of his traveling is, he has no answer. He simply travels – that is who he is.

There is a reason this show is called “Mushishi.” This is not a show about the Mushi – about the pure land of artistic insight, human isolation, and communal existence. And this is not a show about people – about their daily lives and mundane concerns, and the human warmth they often take for granted. This is a show about the place in between. It is about the eternal compromise between the connections we crave and the strangeness that makes us unique, makes us ourselves. As the show itself says, “between dream and reality is the vault of the soul” – it is only by merging our strange individual visions with our solid human connections that true beauty can be found. Mushishi is a show about what makes us different and what makes us the same. It is a show about the ambiguous gift of creation, and the enduring strength of connection. It is a show about people meeting and people parting, hoping they will one day meet again.

Hmmm this essay wasn’t as good as some of your others. I liked it, but the structure felt kind of messy. If anything, it had the feel of an high school English essay to it: “Blah blah blah is a theme in Mushishi. This was shown in episode blah blah blah. The scene in episode blah blah symbolises blah blah, and OH MY GAWD THE CURTAINS WERE FUCKING BLUE DAMMIT”

I did like your main point a lot, though! The idea that Mushishi is a commentary on art as well as life, and that it’s trying to say that the two are intertwined – that’s a pretty common theme across fiction, but I’d honestly never considered it deeply in the context of this particular anime. Which is kind of really short-sighted of me, since many of the episodes, as you’ve pointed out, directly deal with that sort of theme. You can definitely read the conditions of those who are negatively afflicted with mushi as the condition we all get when we become unhealthily attached to the things that normally enrich us, when we become fixated to what is “more real than real”. I feel that phrase pretty much sums up what mushi are.

I just wanted to say that this line really resonated with me in particular. It describes my own worldview, too, being one of those sensitive “writerly” types 😉

Will you be doing any coverage on Mushishi S2, by any chance?

Ouch! Yeah, maybe the structure got away from me a little on this one. I did have some difficulty getting a working outline going for it.

I’m trying to catch up with S2 so I can include it in my weekly posts, but I doubt I’ll be doing full episodics for it. But who knows, I keep accidentally writing full Ping Pong posts…

As I intimated over twitter, I think one can’t write a piece on Mushishi that isn’t a piece on themselves, or even better, a piece relating their experience as they watched Mushishi. There is so much to discuss in the show, and in other ways so little, that the only piece that can capture the show is one that captures yourself in the show.

Regarding your “Favourite Anime list”, I mentioned to you that I felt OreGairu was the most personal choice on the list, which yes, means I don’t think it’s as good as you do, but I could see how much you related to it.

I have been hanging around creative people for many years. I am quite used to hearing of art as a burden, and how a “true artist” is one that must “suffer their burden”, who creates not out of a choice, but because they can’t not create. I think this is an incredibly romantic notion, and one that is in love with itself.

Yes, I do agree, once you begin seeing things, you might wish you had never been gifted them in the first place, but the thought of losing the ability to see what you see, all the connections in life, while remembering that you could see them is almost insufferable. That might be why the notion of memory-loss, especially as a creeping thing, can be so terrifying – we remember our old selves, but we don’t remember all that it entails.

To return us to the original reading as Hachiman or solitude inducing, here is a real question. Hachiman-type characters are often unaware of being Hachimans, as we can see from many of the fans of such shows, and from other such shows. Hachiman though, he knows he’s Hachiman, and he knows his position is “wrong”. Does that excuse his position, or does it damn it further, that he holds onto it even though he knows it as not only ridiculous,

It’s so very… romantic, and feeds right into that “I have seen the truth, so to act as if I hadn’t would be the most terrible thing of all.” – And here’s the rub, it’s impossible to separate such “truths”, whether they are “true”, or “falsehoods” which we often use to shield ourselves. Regardless, the fact is that they are personal, and had become a core part of our personalities, so we will protect them, tooth and claw. Heck, “fans” who adopt aspects of shows and then can’t suffer any attacks on them for they are perceived as attacks on their person operate exactly the same, so one must always be careful of such “truths” and moreover, of treating them so romantically.

Finally, I strongly suggest you read some of the Witches of Lancre novels from the Discworld series by Terry Pratchett. Granny Weatherwax and the witches are aware of the narratives that shape and move the world, and they must live apart from the rest of humanity, their knowledge, and their meta-knowledge, keeps them apart. And yet it is only their relationship to their community that gives them not just energy and validation, but justification, for the somewhat terrible actions they must bring about.

You can adapt, and that is one of the lessons of Mushishi. You can, and sometimes must give up on your “gift”, in order to live with others, and maintain your touch with them. It’s not inability to live as anything else (a quote related to the definition of “The Suffering Artist” above), but more your lack of desire to give up on what you use to define yourself, and sometimes, no matter how noble it truly is, that makes you a Hachiman.

Which brings me to the next point:

Alongside:

Though later you seem to have a conclusion, in this late quote:

First, it seems you are indeed ambivalent. Here, it seems you’re speaking of Mushi, but due to the framing of the piece, it truly is about the gift of insight, and gift of writing.

And here it is not the ambiguous relationship to it that I must question, but the nature of the gift itself. What exactly is your presentation of the author? This isn’t as much a piece on Mushishi as it is about how an author, how you, Bobduh, relate to people through your gift of writing, so I think it’d have been appropriate to spell it out.

Do you think one must be connected to the world to write properly? Yes, I agree. Do you think one must be connected to the world to later impart their “findings”? Yes, also easy to agree with. The bit that you hint at, and which is the meatiest argument, and one that is actually contestable, though I think I agree with it as well is the one you don’t actually spell out, and also the one that is the most Hachiman message of them all, the one so many of us carry over from our youth, and is related to the whole “Better die than lose access to our insights”, and that message is, “Our insights keep us apart from people, and especially our insights about people and their relations.”

It is sometimes hard to relate to people when you see what makes them tick, but then we run into the sad truth – we are both unwilling and unable to give up on our “insights”, but those insights are the very thing that keeps us from connecting to people, which can give us more insights, and which can give us happiness.

To be unhappy we cannot share that “gift”? To be unhappy that we cannot share the “burden”. Romantic, but would we wish to have others cross over, to the land out of sight?

I do like how your final piece on Mushishi returns you to its beginning, to its first episode, taking you full circle. I do wonder though, what would you have written about had the first episode not existed. Probably about Tanyuu. As I myself opened this piece, there are so many things to write about with regards to Mushishi, but the only way to really write a piece about it is a personal one. The author, hidden from the world in his dank abode, collecting pieces of information and disseminating truths, cherishing when people come to call on him? Hm.

You did say that, and the notes I ended up with probably wouldn’t have been sufficient for another read, but man, it’s still a stressful thing to write and release. Haven’t been this stressed about a piece since the Evangelion one.

Undoubtedly true. I think the article skews this point somewhat because Mushishi itself is so dire in its portrayal of the consequences of these choices, but I have to disagree that this is entirely a choice. Personally, my anxiety only goes away just after I’ve created something, and my pride is significantly connected to the catalog of things I’ve made and the proficiency of writing I’ve developed making them. I suppose these are both things that could be “fixed” (maybe, though they’re pretty fundamental), and I suppose my desire not to is a somewhat romantic one, but I don’t think it’s an inherently “wrong” sort of identity. You can frame virtually any set of personal choices as romantic ones, and it’s not surprising to me that writers of all people tend to see romance in their own life choices.

I have! The witches are great.

I actually disagree with this point, and I think it somewhat separates my position from the specific Hachiman one you’re positing here. I love people, and think they’re wonderful, and greatly enjoy creating stories or essays that indicate this. It’s less that I personally feel isolated from people due to having an artistic temperament, and more that I just constantly feel the need to express that urge in lieu of other activities.

I don’t think this really invalidates your general argument here (I agree with a lot of it), but I think it’s a distinction that should be made. It’s more about comfort and passion than it is any perceived “burden of knowledge” about others.

I actually debated between structuring it around this one or the “chasing the rainbow” one, though Tanyuu would also be a good choice. The show hammers on this point a lot – hell, even the first episode of the new season is pretty focused on it.

very self indulgent piece, but then again you’ve earned the right to be. thanks for the writeup

Eh, what can ya do. It was kind of hard to keep this one at arm’s length.

Is it just me, or can most critically acclaimed media be summed up with “Everything is AT fields?”

Even (or especially?) Citizen Kane.

AT fields are pretty key! Human connection’s a tricky thing.

Even if this is true in some ways for most of your posts, this is one of those were you seems to talk about yourself as much as you talk about the show.

Mushishi calls for that sort of interpretation, indeed.

Someone related to art (by commenting it, and even trying it yourself) will evidently take this at heart.

I tend to use the most mundane interpretation. Mushishi as bacteria.

They have a strong effects on people, even if most peoplecan’t see them.

They can have negative or positve effects, but they are essential to life (places without Mushis have childen growing up more difficultly, and more illnesses. In a way, it also works for the art interpretation : A life without art is far more empty).

And the forms of most of the common mushis kinda looks like bacteria too.

The fact that they are so close to Life itself also works.

Well, that’s that freedom of interpretation that is part of Mushishi’s greatness.

Side question :

Have you also seen the special, or are you letting it for latr ?

Yeah, it’s such a rich show. I feel like it combines the universality of ambiguous moral fables with this excellence in craft and a small set of pet themes to just create something incredibly impressive.

And yeah, I’ve seen the special. It was pretty great – I liked how the somewhat longer format allowed the pacing of its first and last act to breathe a lot more, and I loved the sequences where they used that building song to portray the tension of the eclipse beginning and ending. Based on that and the second episode of season 2 (which is as far as I’ve currently gotten), it’s looking like the show’s actually interested in going a bit further outside its dramatic comfort zone than the first season was. I’m really excited to see that continue.

I’ve been excited to see what you took away from this series. I thought it was pretty cool to tie everything into the structure of the first episode. That’s what I like about the series. So many themes bounce around and fit multiple episodes that you can use so many of them as a template to represent the whole series. It’s much more than episodic, it’s beautifully unified.

Tanyu is my favorite character in the series. And the Sea of Writings episode is my favorite for many reasons. It showed that even amongst other Mushishi, Ginko is uniquely kind and pacified in how every other Mushishi can only offer stories of killing. The other is that Tanyu and Ginko are probably my most shipped romance that’s not really a romance. Out of all potential couples that are merely hinted at in anime, they are my favorite.

Also what did you think of the more dark or drastic episodes such as the one with the changeling kids?

Also, before starting the second season, did you watch the OVA?

Tanyuu and Ginko are the best! It is remarkable how much I already like them as a couple, given they only spend one damn episode together.

That changeling episode was something else – I feel like the show in general took kind of a dark turn in the last few episodes, which was interesting. And that episode in particular put forward a more antagonist relationship between human and Mushi than any other… but then again, Ginko may have been deliberately dehumanizing the Mushi just to make the necessary actions a little easier for their “parents.” I dunno. It was certainly a chilling story.

And yeah, I’ve seen the OVA. It was a very solid episode, and I actually feel like the show’s dramatic structure has received a bit of an upgrade in the time it’s been away. Considering I already think this is one of the best shows I’ve seen, I’m excited to see the rest of season two!

Most of the time when I’ve heard discussion of Mushishi there was a lot of focus on how it portrays the relationship between human civilization and nature. You seem to have avoided that, more or less. The lens through which you look at it here is interesting to me, because although I love the show, the nature/humanity thing always kind of kept me at a distance. Because I live in a civilization whose interaction with nature is more concerned with how big of an impact humans have on it, I found it hard to identify with the characters in Mushishi struggling to deal with the impact nature has on them.

The human civilization/nature thing would actually be pretty far down the list of ways I discuss Mushishi. If I weren’t using it to talk about art, I’d probably be discussing it in terms of general human contact or spirituality – if I wasn’t using those, I’d probably talk about the ways various Mushi are metaphors for their associated characters’ emotional issues.

That’s actually what I’ve been thinking about more as I watch the second season. If you’ve seen it, the third episode uses Mushi pretty much directly as a metaphor for the inability to accept loss and grieve, while the second uses Mushi to parallel the actions of the human characters. It’s all pretty clever and poignant stuff!

For me this was probably my favorite piece of yours. It really hit on a lot of interesting ideas about Mushishi that I never really thought of. I think in a large part that is because the show has so many potential themes and messages. If 20 people wrote essays about this show they would all be completely different.

In particular I liked you how connected mushi to art, and how once created it leaves the creator’s control. I know that since you are a writer that particular concept is personal to you, and I could really feel that connection in this piece, which is part of what made it so interesting. I enjoyed how you tied so many of the individual vignettes into that concept, it really made me go back and think about the show in a new light.

I myself always have a hard time discussing mushishi, because it’s both so ambiguous and universal at the same time. The messages one person pulls out are so different from what another person pulls out, that it is often hard to explain your viewpoint on it. In light of that you did a fantastic job making all of your points seem like natural conclusions that anyone could draw from this show. Nothing felt forced, nothing felt thrown in to simply be another example, everything seemed to flow naturally as if it was the most obvious thing. Great job.

Glad to hear you enjoyed it! I couldn’t stop seeing this stuff in the show, so it’s very nice to hear it comes across naturally.

I was curious to see what you would write for this because Mushi-shi is quite different from other animes. There really isn’t a character arc, most character (while defined) come in for an episode and goes, and to be totally honest the main character even now is still mysterious. Ginko reminds me of Nausicaa from The Valley of the Wind in that both are hyper intune with nature and more or less flawless. They bring to the light the flaws in others but themselves are not just protagonists, but (mostly) flawless heroes. Each episode can honestly be a stand alone with most of the characters replaced. But I can’t help but love this series because of its simplicity and beauty. It’s like hearing a folktale told by your grandfather on a rainy day when you were little.

Yeah, every episode creates a comfortable little world. The stories aren’t always soothing, but the atmosphere is remarkable.

Reblogged this on compass on my field trip.