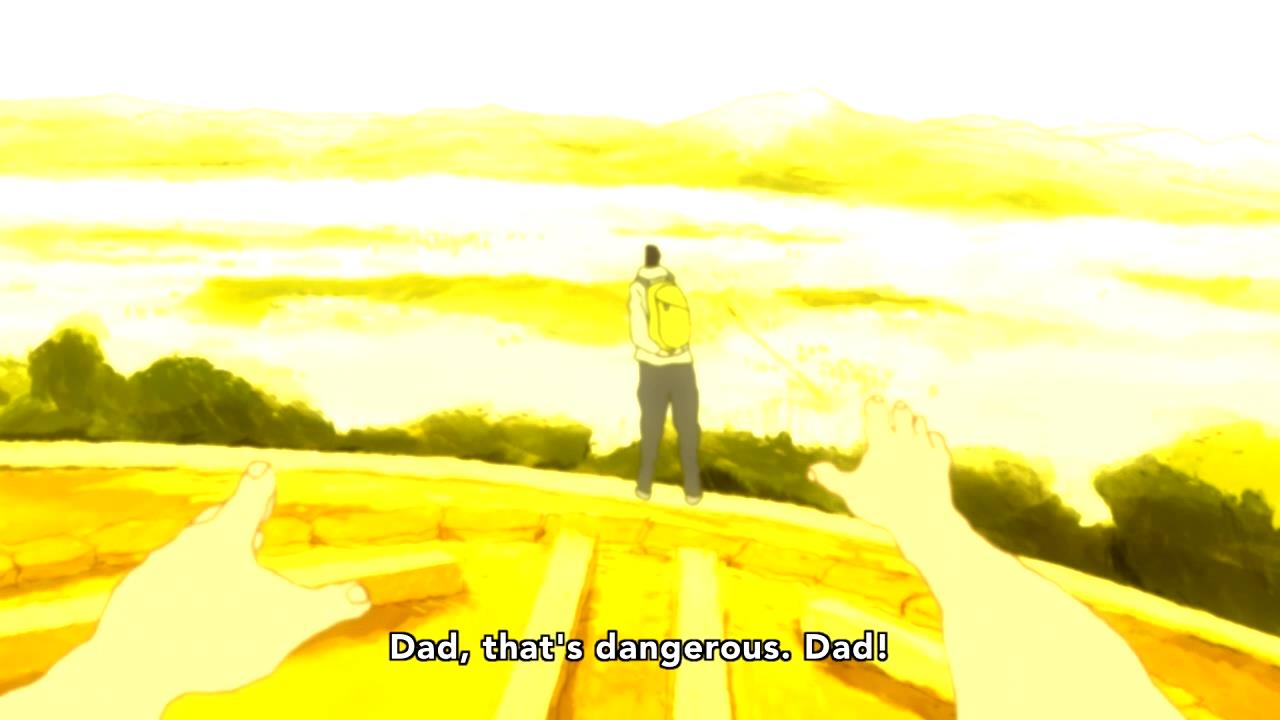

Kazama has been struggling for a long, long time. Ever since the disgrace and death of his father, he’s had it drilled into him that only success matters – that only victory can bring him value or respect. He climbs a slow mountain, finding value in the pain itself. What else can he find value in? He knows victory is just a word, but it’s the only word he knows. His memories of his father are equal parts longing and fear – a desire to embrace his father’s love of life, and a fear of the waiting abyss. The death of his father has made him too afraid to fly.

To a man like Kazama, Peco is both threat and insult. Peco loudly brags about his status as a hero, something Kazama is sure doesn’t exist. Heroes aren’t just powerful warriors, or victors – heroes are defined by how they save others, and Kazama has been taught that you can only save yourself. Perhaps even worse, Peco finds joy in ping pong, and strength in the love of the game. To Kazama, who can only measure his value in the pain he exerts in pursuit of victory, all of this seems like a naive lie, like an ignorant echo of his father’s voice. He must defeat him – he must continue to climb the mountain, defying the abyss and proving there is no other way.

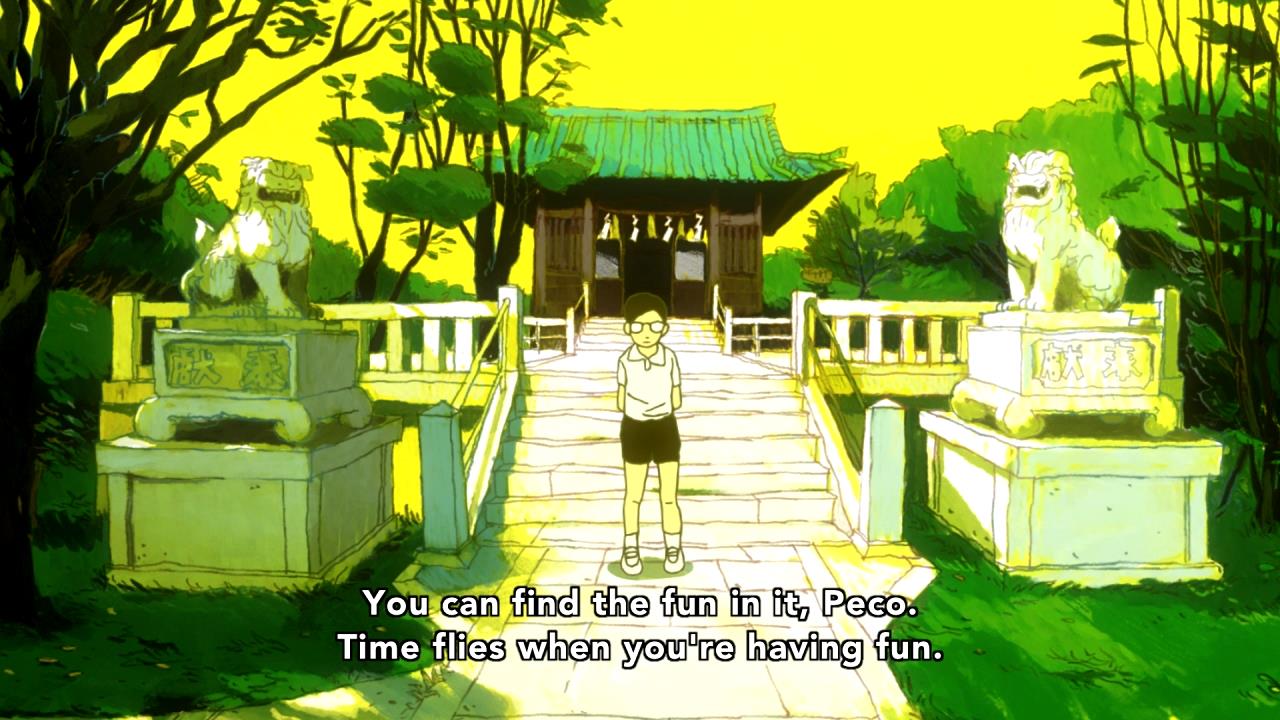

Peco doesn’t really understand much of that – to him, the Dragon just seems like an awesome opponent. Though Peco has always seemed to play for love, his defeat early on proved how flimsy his pride once was – but now, he truly does play for love, both a love of the game and a love of Smile. And even a love of his opponent, in this case – as Peco says, the greater the opponent, the higher he can fly. In the first two games, Peco sinks into fear of a greater opponent, and Kazama is the undisputed champion in the field of fear. But by the third round, Smile’s words finally reach him, and he regains that sense of fun, of love.

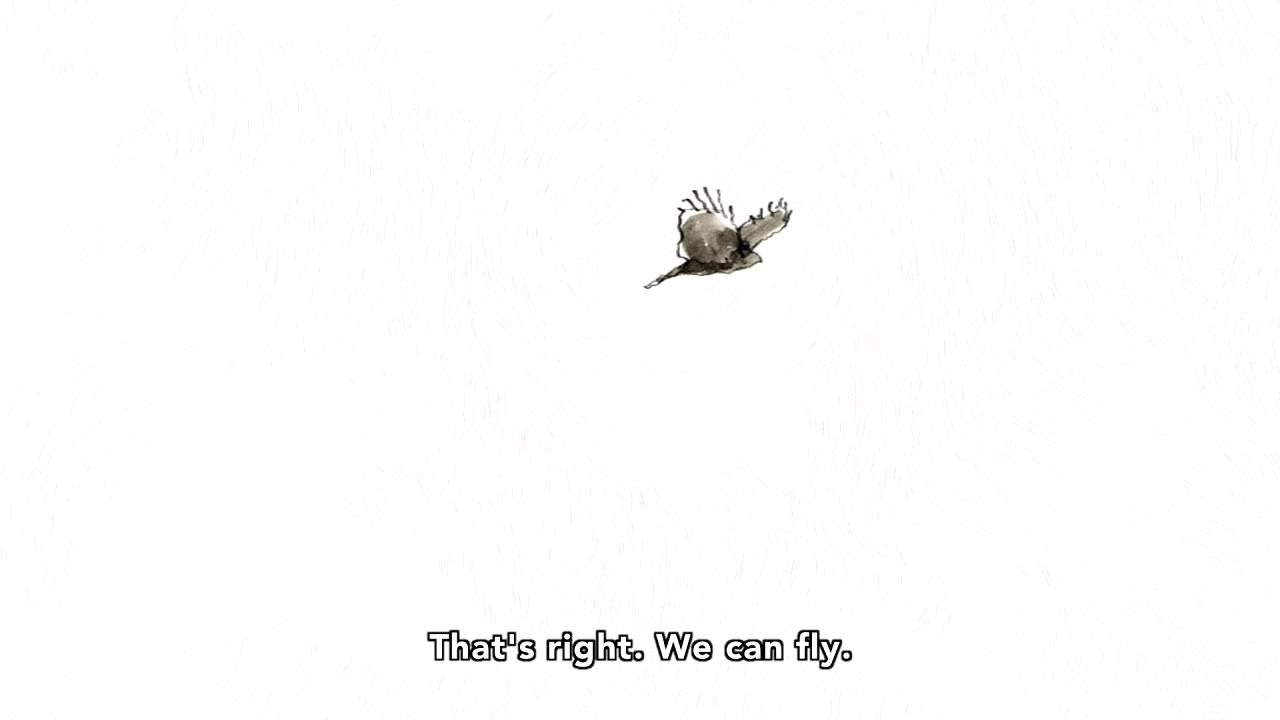

They’re a funny thing, heroes. You’d think they’d be defined by their ability to save others – and that is true, to an extent. But as Wenge’s team-based confidence has already demonstrated, heroism is actually a two-way street – just as heroes make us strong, our belief in heroes is what makes them strong. It is Smile’s belief in Peco that lifts him up, that makes him soar so high. And from that high of an altitude, even Kazama can see him fly – as he climbs up his mountain, fearing the abyss, he can still marvel at the bird in flight. Though the four walls of his bathroom stall encroach, the ceiling is open. Kazama can still look, can still reach, can still dream.

The match between Peco and Kazama ends not in dour dramatics, but in laughter, in a shared love of the sport. Fear defined Kazama’s play, but Peco manages to break through to him, to show him through competition and love that there is joy in these exchanges. Remembering his initial love of the game, a love fostered by his father, he realizes defeat is not death, and the abyss nothing to be feared. Anyone can soar, can be the hero, can join the bird in flight. The bird does not fly because he has wings. The bird flies because he is not afraid to fall.

I loved this episode, and I cannot wait for the finale. Smile vs Peco seems like it shouldn’t be a big deal, what with them playing each other all the time at the start. But this is what the series has been building towards, and this is the first time since they were kids that they will face off for real. Thursday cannot come fast enough.

One of the best things about Ping Pong is how clearly it tells it’s message, both through it’s characters and it’s excellent visual symbolism. For most other shows when I read writeups like yours you can tell a little digging and interpreting was necessary, but Ping Pong just lays it all in the open where anyone can see it.

I’m so excited to see how they handle this finale! The show has built these characters so well, and stressed so strongly how unrelated victory is to their personal journeys, that I can’t really guess how it’ll end.

And yeah, I love how this show uses visual symbolism. More shows should do that! This is anime, this is what this medium can do.

I like how Peco vs Kazama seems to be a parallel to that classic fantasy story: “Hero slays Dragon to save the princess”. Except this time the “princess” is Kazama–nah, Ryuichi himself, who was enslaved by his Dragon persona in a self-built prison.

Apart from that, it also reminded me of Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being–the whole subject of “lightness” vs “heaviness”. Kazama thinks power is heaviness, is burden, is how he must win because that’s his identity. But Peco shows him that true power is lightness: doing something freely but with passion, flying around because his soul is light, very much like how Nietzsche used to described himself.

Kazama wants to win because he thinks it’s his responsibility. Peco wins because he loves the very act of playing–so much so, that he frees Kazama from his own cage and reminds him the beauty and the exhilaration of ping pong.

I’m so happy that this series is going to be a perfect one from first episode to last.

It’s a wonderful feeling to see a show this good end this well. I love how it’s basically skewering the very idea of victory as something to be sought – the “Hero and Dragon” conflict is resolved by both of them embracing the joy of the contest itself, and in light of that, whoever actually wins is irrelevant.

“Though the four walls of his bathroom stall encroach, the ceiling is open.”

http://i.imgur.com/kAB0lbo.jpg

That was a beautiful write-up.

Thank you!

Pingback: Spring 2014 – Week 11 in Review | Wrong Every Time

Pingback: Ping Pong and the Courage to Fall | Wrong Every Time

“The bird does not fly because he has wings. The bird flies because he is not afraid to fall.”

And how can a bird fly, if he has no wings? That is my exact problem with this show. The message it conveys is that talent triumphs over hard work. A few months of practice and love for the sport allows an injured player to completely dominate a national champion who has been playing his entire life. This show completely ignores what is physically possible and instead pits the characters against each other in a clash of ideals, in which the good guys always win, just like any other generic shounen.

“Flying” is not “winning” – it’s “engaging with the world.” Most of the protagonists of this show do lose – repeatedly, in fact. But what they learn is not how to win, but how to lose gracefully, and not let that be a reason to lock themselves away from the world. Winning is arbitrary, but everyone can engage with the world.