I’ve never been much of a sports guy.

Shocking, I know. Somehow, my appreciation of boys kicking or throwing various projectiles could never quite match my love of writing, videogames, and Japanese cartoons. I stayed inside, I played Zelda, I chortled while talking about the “jocks” playing sportball. I was above all that.

My father did not take this easily. Though his day job as an art school administrator wouldn’t indicate a sportball heart, he was indeed a Big Fan, and he did his best to pass his enthusiasm on to his kids. I did terribly in little league, and so baseball was right out. I did mediocrely in soccer, until the C team I was dithering on mutinied and refused to play. I did competently in tennis, but never had much passion for it. There were sports camps and tournaments, with my father always there as spectator or coach. Eventually, he gave up on forcing enthusiasm, and turned instead to my younger sisters. They turned out to be much better “traditional sons” than I was – both of them worked hard and experienced great success as high school soccer players. And I stuck with my nerdier pursuits.

My experience with sports somewhat set the tone with my relationship with my father. We were friendly, but I always felt there were bars I had to clear – that in payment for not quite being the son I was expected to be, I would instead have to prove myself by excelling at being the son I actually was. I would have to prove my passions were valid, my choices were good ones. This was in stark contrast to my relationship with my mother, who’d always been my biggest fan – though she’s also a writer, she works in law, and so my creative work was always a delight to her. In my mind, dad was the one I had to work to impress – though he was in truth a very compassionate man, and his shadow was clearly one built up through my own young insecurities, its emotional place in my life was real.

This came to a head after college, when I returned home with a flimsy English degree and no real career prospects. I pushed through a variety of part-time jobs while trying to make it as a musician, as an author, as a game designer, dreading the career conversations that punctuated all this frantic scrambling. I wasn’t going to give up my dreams, but I didn’t have the answers he wanted, and so our talks remained a tense game of invention defined by permanent distance. What we shared was communal fear over my future, but you can’t bond over a thing like that – not with the person you’ve always seen as the gatekeeper to respectability, anyway. Eventually I got a better job, which was a relief. I also moved out, which was a bigger one. And I read Cross Game.

The easy way to describe Cross Game is “it’s a baseball story that’s really a human story.” Its narrative tracks the journey of Kitamura Kou from elementary school to Koshien, the climactic high school tournament that all young players aspire to. Kou’s family runs a sports supply store next to a batting center, and Kou himself is basically family with the four sisters who live there.

The first thing you need to know about Cross Game is that it is an all-in-one bible of manga storytelling. After the first volume’s shocking twist, nothing else in its narrative will likely surprise you. Its story builds gracefully, its seeming effortlessness a sign of veteran mangaka Mitsuru Adachi’s mastery of his medium. Characters are sketched lightly, and then gather shading over volumes of elaboration. Conflicts build in slowly gathering refrains, pulling together character arcs and then shattering in small climaxes, only to rebuild again. Love and loss and family and passion are not declared through stirring speeches, they are simply the inescapable human truths of a well-told coming of age.

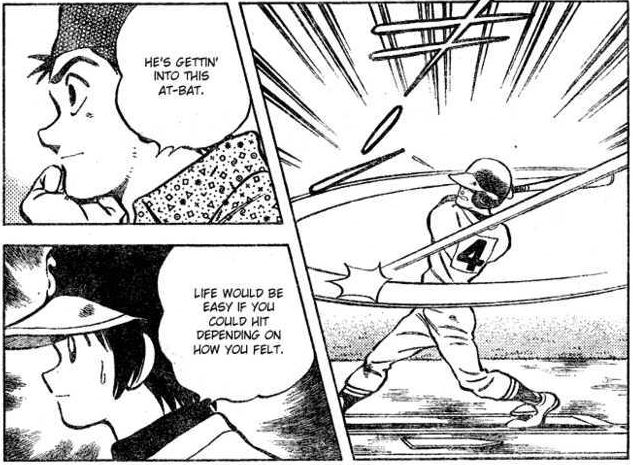

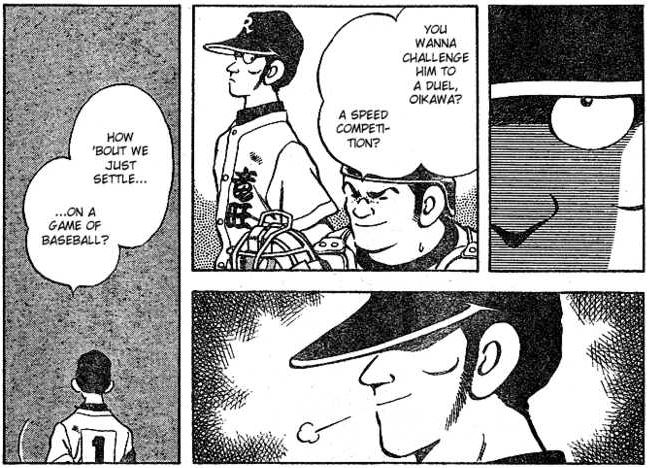

“Baseball as human story” isn’t just a reductive description – it is actually through the lens of baseball that Cross Game’s characters reveal their humanity. Though I’ve never been a person who’s understood the passion people feel for sports, Cross Game makes that passion real. This partially comes down to Adachi’s tremendous visual storytelling. His paneling, his sense of visual economy, the way he paces climactic innings and even entire games, makes the drama the characters experience more real than any actual game could be. The drama of baseball is not heightened – though Cross Game’s characters are excellent players, they are not superhuman. Instead, the drama is clarified – through Adachi’s careful eye for motion and clear love of the sport, the key variables of dramatic conflict are made transparent and visceral. The storytelling is good enough at illuminating true drama that it never has to embellish.

Through Adachi’s meticulous work, the emotional bonds these characters build through baseball become natural, become obvious. A single great pitch can be a declaration of earnest trust. A humble play can be a sacrifice that demonstrates loyalty and character. A hard-fought game can be a memorial to an absent friend. Baseball is what brings this family together. The bonds they form and confirm through baseball are emotionally true.

Just over a year ago, I learned my father has Parkinson’s disease. It’s a terrible thing, and I don’t really want to labor over it, but the knowledge of it made something shift for me. I know my father, and I respect him greatly, but we’ve never really had that father-son bond that TV families seem to take for granted. I want that – I want to know I’ve made the most of my time with him, that our relationship is not one shadowed by regret. So when he very surprisingly asked if I wanted to go to a baseball game with him, I said yes.

Cross Game didn’t actually teach me to understand baseball, but it did show me there is a human truth there. That a pitcher’s struggle can be poignant drama all on its own, and that that drama can mean something more than a ball hitting a bat. And though Adachi didn’t quite explain every detail of the action, my dad was very willing to fill in the rest. I don’t gasp at every pop fly now – I know most of them are doomed from the outset. I can sort of guess how a pitcher is doing, or what batters I should look out for. I can cheer with my dad without faking it – the newly understood truth of the drama makes that common elation real.

Cross Game helped me understand sports, and through that helped me find a common truth with my father. I don’t think I could ask more of a story than that.

Wow. That was Stirring. I’m genuinely misty-eyed from reading this. It seems you haven’t had much chance to do your essays given how busy you are with all of your other writing, and damned if that isn’t a shame because they’ve always been your best works. This one works as both a winning advertisement of Cross Game, and a sterling example of why people should donate to that patreon of yours!

I am very sorry to hear about your father. As someone with a similarly awkward and distant relationship with his father, yeah – you’ve nailed what it feels like. It really is a self-inflicted thing, a basic sub-conscious instinct which scolds you for not following that same path. I think it goes without saying, but if he reads these posts, he should be very proud of you.

Sorry, yes. Excellent post!

Thank you for your kind words! And yeah, I’d like to have time to keep up with the essays along with everything else. My writing is getting faster over time, so we’ll see. Gotta be strong like Ema!

That was a great and surprisingly personal read. I hope everything goes well with you and your father and thanks for another great read!

Wonderful. Thanks for sharing that. Cross Game is indeed a baseball story that enlightens the human condition and celebrates good storytelling and the power of love.

Glad you enjoyed it. Cross Game is one of those stories I can always come back to and have it feel rewarding.

Great piece. There’s an excellent book on Japanese baseball, particularly through the lens of American players, called “You Gotta Have Wa” by Robert Whiting. It was written in the early 90’s and thus features some of its own America-Japan tensions and agendas. Even so, it’s perceptive of not only baseball in Japan but underlying cultural elements that make baseball as big as it is, and the book is worth a read if you have the time. Your comments about the personal, serious, or symbolic nature of a play are similar to some of the material in the book.

Best of luck with your Patreon, anything that lets you write more.

That sounds interesting! Cross Game is much more of a personal story, but I’ve heard all sorts of not-so-great things about the nature of high school baseball in Japan, and the culture surrounding it. It’s a strange thing.

Really wonderful essay. I haven’t read or seen Cross Game. But it sounds right up my alley. I can’t help but compare my relationship with sports with yours. I grew up without a father, which is fine, and I always loved sports. Every sport has something whether its cricket or basketball, something that makes it unique. I love watching people who have spent their years one a singular activity find glory in that. It seems just somehow. I Never played though, I was kind of too poor to try anything organised, but I always dreamed of that moment where your on the field and look in the stands and see someone familiar. Who would invariably be proud. Sorry about your father, I hope you find that.

I’m sorry to hear that your dad was diagnosed with Parkinson’s. I have a mom who was recently diagnosed with cancer, and so this piece hit close to home.

That said, even without that connection, I think this is one of best essays you’ve written. Thanks for sharing it. 🙂

When I was around 8 years old my father made a bet with me that by the time I was 18 I would like sports more than I like cartoons. And even though it’s kind of funny to look back on, I always feel guilty that I can’t talk with him about how Michigan’s chances look this year, or how the Red Wings did, especially since I am his only child. Thanks for sharing this essay, I know personal writings can’t be the easiest to do. I hope you and your father continue to create wonderful memories together and I hope your writing journey is long and fruitful!

I think I’ll start Cross Game today.

Magnificent is the only word I can use to describe how great this piece is. Strangely enough, I didn’t do all that well in sports too. The conflict was brought by my parents concerns about me “not having enough friends”. I’m truly glad that we were able to overcome that stage with a smile on our faces.

Feel really sorry about your father’s condition, I wish you and your family the best of luck.

As always Bobduh, keep writing like this. We all love it!

PD: I’m so starting Cross Game now! (Perhaps I’ll check other Mitsuru Adachi works …)

Oh jeez, you live and Boston and aren’t a sports fan? That must be friggin’ exhausting. I mean, I’m not exactly one of those guys who covers themselves in bodypaint for every home game, but I can’t imagine how awkward it must be to live in town and have to feign interest in the Red Sox…

For me, the story that made me feel this way was Silver Spoon, especially when they got into the family business and making your own decisions area. It made me tear up once or twice.

As a son who isn’t really close to his father, I understand your pain. The pain of not living up to his expectations is often hard-pressed and stressful. I would give you some helpful advice, but I don’t have my shit together either. Other than that, thanks for the essay.